Author: Jonathan M Jones / Editor: Steve Fordham / Reviewer: Stewart McMorrran, Nadarajah Prasanna, Rafeeq Ahmed Sulaiman / Codes: R2 / Published: 18/06/2021 / Reviewed: 13/03/2025

Context

The relative incidence and mortality of shock varies greatly depending on the population and the cause.

Worldwide, the greatest number of deaths from shock probably occurs in children under five years old. This is due to hypovolaemia as a result of diarrhoeal illness. [1]

By contrast, the Office of National Statistics (2005) recorded about 25 deaths from diarrhoeal illness in the same age group in the UK in 2005. [2]

Anaphylaxis causes about 20 deaths per year in the UK. [3]

In the United States, sepsis is a significant cause of mortality, with approximately 270,000 deaths annually. [4]

Cardiogenic shock is closely linked to high early death rates, with mortality often exceeding 50%. [5]

Definition

Baron, quoting Moore, [6] on the pathobiology of sepsis commented:

Unfortunately for our campaign to eliminate the word shock. and thus help to untangle the confusion between sepsis and trauma there is no other monosyllable that quite does the job. Still, we would be better off without the word, and our teaching would be clearer if we never used it, since such a departure would cause each surgeon or physician to specify causes and mechanisms rather than contenting himself with the diagnosis of shock, implying that all patients in such a state are essentially the same.[6]

Shock is a somewhat lazy shorthand to describe the state that results when circulatory insufficiency leads to inadequate tissue perfusion and thus delivery of oxygen to the tissues of the body. [7]

What Causes Shock?

Shock can be the result of numerous different pathophysiological processes that can be broadly accommodated within four somewhat artificial categories: hypovolaemic, distributive, obstructive and cardiogenic. [8] (Table 1)

Irrespective of the cause the inadequate delivery of oxygen to tissues results in a failure of aerobic metabolism leading to end organ dysfunction.

The situation becomes more confusing if examples of dysoxia are considered to be types of shock. Cyanide poisoning is a classic example wherein mitochondria are prevented from using oxygen. Such disease states are outside the remit of this module as the primary problem is not one of circulatory compromise.

| Hypovolaemic (inadequate circulating volume secondary to fluid loss) |

Distributive (inadequate perfusion secondary to |

|

|

|

Obstructive (inadequate cardiac output as a result of mechanical obstruction) |

Cardiogenic (inadequate cardiac output as a result of cardiac failure)

|

|

|

Learning bite

Shock describes a pathophysiological state with many different causes, NOT a specific diagnosis.

The pathophysiology underlying shock varies enormously from cause to cause. This section will focus on some basic underlying concepts.

What determines oxygen delivery?

The pathophysiology underlying shock varies enormously from cause to cause.

Take a moment to think about the key factors that determine global oxygen delivery i.e. the amount of oxygen leaving the left ventricle every minute. [7,9]

Global oxygen delivery is determined by cardiac output (CO) and arterial oxygen content (CaO2).

CO is heart rate (HR) x stroke volume (SV).

The vast majority of oxygen carried in the blood is bound to haemoglobin. Only a tiny proportion is in solution (measured by PaO2). So, the main determinants of arterial oxygen content are oxygen saturation and haemoglobin concentration.

For practical purposes global oxygen delivery can be calculated as:

(HR x SV) x [Hb]g/dl x 10 x 1.34 x sO2 ml/l

Where:

- The 10 is to convert g/dl of Hb to g/l

- The 1.34 represents the amount of oxygen (in ml) carried by one gram of 100% saturated haemoglobin.

What happens when oxygen delivery is inadequate?

In very simple terms, cells run on adenosine triphosphate (ATP). ATP is produced by respiration, either aerobic or anaerobic. Anaerobic respiration is about 18 times less efficient than aerobic. In the absence of adequate oxygen delivery, cells run out of energy and cease to function effectively and, if the situation is not corrected, die. On the macroscopic level this is apparent in organ dysfunction and failure.

Compensation and decompensation

The body has a range of compensatory mechanisms to cope with a reduction in oxygen delivery as a result of circulatory compromise. These include the ability to dramatically increase the amount of oxygen extracted from the blood the oxygen extraction ratio (OER). The initial clinical signs and symptoms that suggest shock is developing are the result of the compensatory mechanisms; the later features are those of organ dysfunction as the compensatory mechanisms fail. If the causative pathology is not identified and corrected quickly enough the uncompensated shock state will progress to a situation of irreversible damage.

Learning Bite

There is a window of opportunity in which to identify and treat a shock state after which the damage will become irreversible.

Assessment and management of the patient must follow an ABCDE approach and involve 4 key steps that should ideally occur concurrently:

- Recognition of the degree of physiological compromise

- Identification of the cause

- Correction of the physiological deficit

- Treatment of the underlying cause

A focussed history must be obtained and examination performed concurrently with resuscitation. Some specific clinical findings merit further discussion:

Heart Rate

Why does heart rate increase in most types of shock?

Cardiac output (CO) is heart rate (HR) x stroke volume (SV). A reduction in CO causes reduced activity of arterial baroreceptors causing increased sympathetic and reduced parasympathetic activity. [10] Heart rate increases and cardiac output is restored towards normal.

In what types of shock does the heart rate not increase?

An increase in heart rate is an early sign of compensation but its absence does not exclude significant compromise. While the majority of patients with acute blood loss demonstrate the typical tachycardic response, it is important to be aware that as many as 30-35% may present with an initial relative bradycardia, i.e. heart rate not in excess of 100 beats/min. [11]

This is in addition to patients on beta-blockers who are pharmacologically prevented from mounting a tachycardia, and those in whom a tachycardia may go unrecognised as their normal resting heart rate is lower than average, for example athletes. Bradycardia may, of course, be the cause of the shock state, for example complete heart block, beta-blocker or calcium antagonist overdose. Neurogenic shock is usually typified by an absence of tachycardia, too.

Learning bite

Absence of tachycardia does not rule out haemorrhagic shock.

Skin

How can examination of the skin aid the assessment of the degree of physiological compromise? What clues to the differential diagnosis may be available?

How can examination of the skin aid the assessment of the degree of physiological compromise? What clues to the differential diagnosis may be available?

A reduced CO vasoconstriction caused by increased sympathetic activity will divert blood away from the peripheral circulation leading to cool peripheries.

Capillary refill is a useful test in assessing dehydration in diarrhoeal illness in children and has some value in paediatric trauma but is of questionable value in adult patients [12,13].

Sweating as a result of increased sympathetic activity may produce clamminess (diaphoresis).

In distributive shock, the skin may be warm and dry: neurogenic shock (loss of sympathetic tone as a result of cord injury) leads to vasodilatation and an absence of sweating. In UK trauma patients, neurogenic shock occurs in about 20% of patients with cervical cord injuries (7% for thoracic and 3% for lumbar) at presentation. [14]

Anaphylaxis is characterised by patchy or generalised erythema, urticaria and angioedema but skin or mucosal changes may be absent in up to 20% of patients. [15]

The image displays urticarial rash (hives).

Sepsis

In early sepsis, the skin may be warm but as the condition worsens peripheral perfusion is reduced. In children, cool hands and feet are early findings in meningococcal sepsis and the reversal of the proximal progression of cool skin gives some indication of the adequacy of resuscitation. [16]

The skin may provide clues as to the causative organism, such as purpura in meningococcal infection and generalised erythaema in toxic shock syndrome.

A thorough examination is needed to identify possible occult sources.

In the image, the meningococcal bacterium is the diplococcus to the left of the nucleus of the large cell.

Respiratory Rate

Respiratory rate is an excellent marker of physiological compromise that is poorly utilised and often overlooked. [17]

Respiratory rate may be increased because of hypoxia (e.g. in pneumonia) but will often remain elevated despite correction of arterial O2 content (CaO2) as worsening perfusion generates a metabolic acidosis requiring respiratory compensation.

Learning Bite

Pay attention to the respiratory rate and never ignore tachypnoea

Blood Pressure

How useful is blood pressure as a marker of shock?

It is a common mistake to equate a normal blood pressure with the absence of shock. The bodys ability to compensate means blood pressure is maintained until a late stage in the progression from physiological insult to an irreversible shock state. [18] This is demonstrated well by acute blood loss.

| Class of shock | Class I | Class II | Class III | Class IV |

| Volume of blood loss (ml) | Up to 750 | 750-1500 | 1500-2000 | >2000 |

| Volume of blood loss (%) | 0-15% | 15-30% | 30-40% | >40% |

| Heart Rate | <100 | >100 | >120 | >140 |

| Blood Pressure | Normal | Normal | Decreased | Decreased |

| Pulse Pressure | Normal or increased | Decreased | Decreased | Decreased |

| Respiratory Rate | 14-20 | 20-30 | 30-40 | >35 |

| Mental State | Slightly anxious | Mildly anxious | Anxious, confused | Confused, lethargic |

Not until 30-40% of the circulating blood volume is lost does the blood pressure begin to fall. Note also a reduction in pulse pressure occurs before a reduction in systolic BP as the diastolic increases in response to vasoconstriction.

The mean arterial pressure (MAP = (systolic + 2 x diastolic)/3) is a better representation of organ perfusion than the systolic. A MAP of 65mmHg is considered to be sufficient for organ perfusion in a healthy adult.

Conscious level and Urine Output

Conscious level may be reduced for a host of reasons in the acutely unwell patient but it is vital to bear in mind that alterations in conscious level may be a result of inadequate cerebral perfusion. The combative drunk should only be assumed to be a combative drunk once other pathologies have been realistically excluded.

Urine output is of little use in initial assessment but any patient who is shocked should be catheterised earlybeware of urethral injury in traumato provide an indication of the adequacy of resuscitation over time. In some patients, urine output may be misleading; for example, ongoing osmotic diuresis in a patient with diabetic ketoacidosis despite shock.

Learning Bite

Don’t be fooled by seemingly normal physiology that may be concealing significant compensated shock.

The majority of the investigations in a shocked patient will be focused on identifying the cause of the shock, for example FAST scan in trauma, ECG in cardiogenic shock and echocardiography in massive pulmonary embolus.

It is well recognised in trauma that reliance on physiological parameters such as BP and urine output will lead to under-resuscitation in many patients, and the preceding sections have highlighted that, in particular, a falling blood pressure is a late sign in shock. [19, 20]

Blood lactate

Failing oxygen delivery leads to anaerobic respiration which generates lactate. [21]

A lactate level of greater than 4mmol/l is associated with increased ICU admission and mortality in normotensive patients with sepsis. Those with higher lactate clearance at 6 hours have an improved outcome. [22]

It is unclear whether or not lactate levels on admission are a useful predictor of outcome in trauma patients [23,24]. Normalisation of lactate with resuscitation does correlate with improved survival in trauma, [25] surgical [26] and post-cardiac arrest patients [27] but the timescale over which normalisation occurred in these studies (24-48 hours) makes the existing evidence less relevant to initial resuscitation in the ED setting.

Base excess and bicarbonate levels offer some guidance to the degree of compromise and adequacy of resuscitation but they can be normal in a proportion of patients with significantly abnormal lactate levels in sepsis. [28] Similarly, anion gap has been shown to be a poor marker for lactic acidosis in the ED. [29]

Learning Bite

Blood lactate is a useful marker of severity in shock states

Central venous oxygen saturation

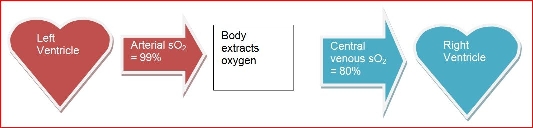

As oxygen is extracted from the blood, the oxygen saturation falls. Consequently, the oxygen saturation of blood returning to the lungs (i.e. blood from the pulmonary artery) can give an indication of total body oxygen extraction.

Usually, this mixed venous blood is around 70-75% saturated SvO2. [30] If it falls below this figure, oxygen extraction has had to increase. In shock states this is usually because oxygen delivery has become inadequate. Demand exceeds supply.

In the ED practice, sampling SvO2 is impracticable. Consequently, interest has focussed on the usefulness of central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2), which tends to be about 5-7% higher. Rivers work on early goal-directed therapy [31] has incorporated ScvO2 as a guide for blood transfusion and inotropic support with a survival benefit and its use is also supported by the Surviving Sepsis campaign.

It should be noted however that in sepsis in particular, ScvO2 can be misleading. As sepsis progresses, oxygen extraction by the tissues becomes less and less efficient and the blood returning to the heart remains oxygenated. In this situation, a normal or high ScvO2 can reflect a worsening clinical picture.

Learning Bite

Don’t be falsely reassured by a normal ScvO2 it may simply represent the tissues inability to utilise oxygen.

Fig 1. The situation in a healthy individual

Fig 2. The situation in a shock state where inadequate tissue perfusion has resulted in a reduction in usual oxygen delivery necessitating an increase in oxygen extraction. This is reflected in a fall in the central venous blood saturation.

Once a shock state is recognised, treatment must focus on reversing the physiological deficit (resuscitation) and treating the cause.

Other sessions will provide much more detail on treatment of specific types of shock.

Frequent clinical reassessment following each intervention will give an indication of the patients response. The response will be rapid, transient or none.

If the response is not satisfactory, consideration must be given to:

- The adequacy of resuscitation so far

- The accuracy of the diagnosis

- The need for immediate definitive treatment (e.g. decompression of tension pneumothorax)

- The need for more invasive cardiovascular monitoring

Learning Bite

Planning and providing definitive treatment tailored to the specific diagnosis must accompany resuscitation

In general, an aggressive early goal-directed approach to maximise oxygen delivery is indicated as in sepsis and early management of sick surgical patients although caution may need to be exercised in some situations. Penetrating chest trauma is such an example, where normalisation of blood pressure with fluid resuscitation prior to surgical haemostasis may worsen the outcome. [31,33] If presentation or recognition of the shock state occurs too late goal-directed therapy may be counterproductive. [34,35]

In the majority of cases, the initial and critical element of therapy (together with high flow supplemental oxygen) will be fluid boluses. These should be small volumes (e.g. 250ml), given quickly (i.e. over 510 minutes) with reassessment after each. There is no evidence that ordinary crystalloid (normal saline or Hartmanns) is inferior to colloid. [36]

Given the key role of haemoglobin concentration in determining oxygen delivery it is important that it is maintained with judicious transfusion. [31] Excessive transfusion is unwise as it has been found to be of no benefit and possibly a risk in critically ill patients. A reasonable target is around 79g/dl in otherwise healthy non-trauma patients. [37,38]

Consideration must be given to early intubation and ventilation in many shocked patients. Oxygen consumption can be dramatically reduced by taking over the work of breathing. [30] In septic patients, increased capillary permeability may mean that necessary fluid resuscitation leads to pulmonary oedema a fact that is recognised more widely in the paediatric population where guidelines emphasise the need to consider intubation once fluid resuscitation exceeds 40-60ml/kg. [40]

With the exception of adrenal insufficiency (Addisonian crisis) which should be considered in all hypotensive patients where there is no apparent cause, particularly those on corticosteroids and if there is both unexplained hyponatraemia and hyperkalaemia there is no role for steroid use in the initial resuscitation and treatment of a shocked patient.

- Shock is a simplistic concept for a pathological state that can arise from a whole range of different disease processes. It is not a diagnosis in itself.

- Shock can be subdivided into hypovolaemic, distributive, obstructive and cardiogenic causes.

- Global oxygen delivery is determined by cardiac output and arterial oxygen content, but perfusion of individual organs depends on many other factors.

- Initial compensatory responses can conceal the developing shock state from the clinician who relies on simple measures such as blood pressure and heart rate.

- Failure to intervene promptly enough will allow progression to an irreversible state characterised by multi-organ failure.

- Blood lactate can be a useful adjunct to initial clinical assessment.

- Resuscitation and definitive treatment should be contemporaneous and must be tailored to the specific diagnosis.

- An increasing evidence base supports the role of early goal directed therapy in sepsis.

- Hobson MJ, Chima RS. Pediatric Hypovolemic Shock. The Open Pediatric Medicine Journal, 2013, 7, (Suppl 1: M3) 10-15.

- Supporting information for mortality statistics, which present figures on deaths registered in England and Wales in a specific week, month, quarter or year. Office for National Statistics. Last revised: 10 October 2024.

- Pumphrey RS. Lessons for management of anaphylaxis from a study of fatal reactions. Clin Exp Allergy. 2000 Aug;30(8):1144-50.

- Rhee C, Dantes R, Epstein L, Murphy DJ, Seymour CW, Iwashyna TJ, Kadri SS, Angus DC, et al. Incidence and Trends of Sepsis in US Hospitals Using Clinical vs Claims Data, 2009-2014. JAMA. 2017 Oct 3;318(13):1241-1249.

- Jung RG, Stotts C, Gupta A, Prosperi-Porta G, Dhaliwal S, et al. Prognostic Factors Associated with Mortality in Cardiogenic Shock A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. NEJM Evid. 2024 Nov;3(11):EVIDoa2300323.

- Moore FD. Shock and sepsis: some historical perspectives. Surg Clin North Am. 1969 Jun;49(3):481-7. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)38832-6.

- Rivers E, Otero R, Nguyen H. Approach to the patient in shock. In Emergency Medicine: A comprehensive study guide. Eds Tintinalli J, Kelen G, Stapczynski J 6th Ed New York 2004 McGraw Hill.

- Hinshaw LB, Cox BG. The fundamental mechanisms of shock, New York, 1972. Plenum Press.

- Levy MM. Pathophysiology of oxygen delivery in respiratory failure. Chest. 2005 Nov;128(5 Suppl 2):547S-553S.

- Guyton AC and Hall JE. Textbook of medical physiology. 13th Ed. London. Saunders 2015.

- Thomas I, Dixon J. Bradycardia in acute haemorrhage. BMJ. 2004 Feb 21;328(7437):451-3.

- Steiner MJ, DeWalt DA, Byerley JS.Is this child dehydrated? JAMA 2004;291:2746-2754.

- Lewin J, Maconochie I. Capillary refill time in adults. Emergency Medicine Journal 2008;25:325-326.

- Taylor MP, Wrenn P, ODonnell AD. Presentation of neurogenic shock within the emergency department. Emergency Medicine Journal : EMJ. 2017 Mar;34(3):157-162.

- Working Group of the Resuscitation Council UK. Emergency treatment of anaphylaxis: Guidelines for healthcare providers. Resuscitation Council UK, 2021.

- Thompson MJ, Ninis N, Perera R at al. Clinical recognition of meningococcal disease in children and adolescents. Lancet 2006; 367:397-403.

- NCEPOD. An Acute Problem? May 2005.

- Fukui S, Higashio K, Murao S, et al. Optimal target blood pressure in critically ill adult patients with vasodilatory shock: a protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2021;11:e048512.

- Advanced Trauma Life Support. 10th Edition. American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. 2019.

- Marik PE. The optimal endpoint of resuscitation in trauma patients. Critical Care (London, England). 2003 Feb;7(1):19-20.

- Huang TY. Monitoring oxygen delivery in the critically ill. Chest 2005;128;554-560.

- Nguyen HB, Loomba M, Yang JJ, et al. Early lactate clearance is associated with biomarkers of inflammation, coagulation, apoptosis, organ dysfunction and mortality in severe sepsis and septic shock. J Inflamm (Lond). 2010 Jan 28;7:6.

- Dunne JR, Tracy JK, Scalea TM, Napolitano LM. Lactate and base deficit in trauma: Does alcohol or drug use impair their predictive accuracy? J Trauma 2005;58(5): 959-966.

- Pal JD, Victorino GP, Twomey P, Liu TH, Bullard MK, Harken AH. Admission serum lactate levels do not predict mortality in the acutely injured patient. J Trauma. 2006 Mar;60(3):583-7; discussion 587-9.

- Abramson D, Scalea T, Hitchcock, R et al. Lactate clearance and survival following injury. J Trauma 1993; 35(4):584-589.

- McNelis J, Marini CP, Jurkiewicz A et al. Prolonged lactate clearance is associated with increased mortality in the surgical intensive care unit. Am J Surg 2001;182(5): 481-485.

- Donnino NW, Miller J, Goyal N et al. Effective lactate clearance is associated with improved outcome in post cardiac arrest patients. Resuscitation 2007;75(2):229-34.

- Otero RM, Nguyen HB, Huang DT et al Early goal directed therapy in severe sepsis and septic shock revisited. Concepts, controversies and contemporary findings. Chest 2006;130:1579-1595.

- Adams BD, Bonzani TA, Hunter CJ. The anion gap does not accurately screen for lactic acidosis in emergency department patient. Emerg Med J 2006;23:179-182.

- Chetana Shanmukhappa S, Lokeshwaran S. Venous Oxygen Saturation. [Updated 2024 Sep 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-.

- PRISM Investigators; Rowan KM, Angus DC, Bailey M, et al. Early, Goal-Directed Therapy for Septic Shock A Patient-Level Meta-Analysis. N Engl J Med. 2017 Jun 8;376(23):2223-2234.

- Dellinger R, Levy M, Carlet J et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008. Crit Care Med 2008;36(1):296-327.

- Bickell WH, Wall MJ, Pepe PE et al. Immediate versus delayed fluid resuscitation for hypotensive patients with penetrating torso injuries. N Engl J Med 1994;331:1105-9

- Gattinoni L, Brazzi L, Pelosi P et al. A trial of goal-oriented haemodynamic therapy in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med 1995;333:1025-32

- Kern JW, Shoemaker WC. Meta-analysis of haemodynamic optimization in high risk patients. Crit Care Med 2002;30(8):1686-92.

- Perel P, Roberts I. Colloids versus crystalloids for fluid resuscitation in critically ill patients. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 1997, Issue 4. Art.no: CD000567. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000567.pub3. (Last substantive update July 2007).

- Hebert P, Tinmouth A, Corwin H. Controversies in RBC transfusion in the critically ill. Chest 2007;131:1583-1590.

- Task force for advanced bleeding care in trauma. Management of bleeding following major trauma: a European guideline. Crit Care 2007;11:R17.

- Singer M. Catecholamine treatment for shock equally good or bad? Lancet 2007;370:636-637.

- Pollard AJ, Nadel S, Ninis N, Faust S, Levin M. Emergency management of meningococcal disease: eight years on. Arch Dis Child 2007;92:283-286.

- Peacock WF and Weber JE in: Tintinalli JE, Kelen GD, Stapczynski JS Eds Emergency Medicine A Comprehensive Study Guide. New York, NY: McGraw Hill 2004 242-247.