Author: Gavin Lloyd / Editor: Gavin Lloyd / Reviewer: David Leverton, Gavin Lloyd / Code: CC2 / Published: 15/07/2023

Context

Pain is the most common presenting complaint to the ED and you should safely and effectively relieve pain in a timely fashion.

There is good evidence to suggest emergency physicians internationally do not perform well in terms of this objective. It is no surprise that two of the three College national audits in 2008 related to analgesic delivery.

This session addresses analgesic delivery. You will be required to devise appropriate pain relieving strategies in adults with musculoskeletal, cardiac and abdominal pain.

The Pathophysiology and Psychology of Pain

How can the perception of pain be explained patho-physiologically?

Simply put, tissue damage at a cellular level results in a release of chemicals which stimulate pain receptors. These pain receptors are able to produce an electrical impulse which is transmitted via a peripheral nerve fibre to the spinal cord and then to the brain where the impulse is perceived as pain.

Tissue damage

Fig 1 An example of tissue damage

Tissue damage may be:

- Mechanical (Fig 1)

- Thermal

- Chemical

- Electrical

- Metabolic (e.g. hypoxaemia, hypoglycaemia)

Chemicals are released as a result and stimulate pain receptors. Prostaglandins, which may be produced as a consequence of the injury, sensitize the pain receptors to these chemicals.

Tissue damage drives pain hypersensitivity peripherally through the release of chemicals due to direct cell damage or release from nearby platelets or mast cells. These include the following: ATP, bradykinin, prostaglandin, serotonin, histamine and hydrogen ions.

Chemicals such as substance P and Calcitonin Gene Related Peptide (CGRP) increase the release of these chemicals via localised vasodilation and mast cell degranulation.

Pain receptors

Fig 2 Pain receptors

The pain receptors, sometimes called nocioreceptors, are distributed throughout the body skin, viscera, joints, meninges, muscle etc. (Fig 3).

Think of them as free nerve endings.

They produce an electrical impulse and connect to peripheral nerve fibres.

Peripheral nerve fibres

Peripheral nerve fibres transmit the electrical impulse to the dorsal horns of the spinal cord.

Ascending tracts within the spinal cord

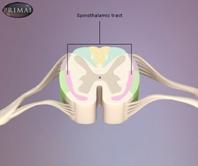

Fig 3 Spinal cord with spinothalamic tract (ascending tract) labelled

Ascending tracts within the spinal cord transmit impulses to the brain (Fig 3).

The brain

Fig 4 The brain and neural pathways

The brain is where pain is perceived (Fig 4). The psychology of pain (or scientifically, the discreet cognitive pathways involved in the interpretation of painful stimuli) remains a mystery.

We are aware that, in no particular order, emotion (especially fear and anxiety), environment, culture, education, beliefs, personality and previous experiences can all have an influence on how we perceive pain.

Indeed, distraction techniques, hypnosis, the placebo effect and some medications act upon the brain, rather than at any other site for their analgesic effect.

Further, physiologists have identified descending tracts from the brain to the dorsal horns of the spinal-cord, that are likely to downregulate pain impulses.

Visceral pain pathways

Fig 5 Visceral pain pathways

Visceral pain pathways involve the gut, heart and lungs etc. (Fig 5). They are more crude and result in poorer localisation of pain (referred pain).

Examples include patients with ischaemic heart pain presenting with jaw, shoulder or arm pain and patients with free peritoneal fluid (such as in ruptured ectopic pregnancy) presenting with shoulder tip pain.

The intensity of a patients pain is clearly subjective. Facial expression and demeanour may give some clues but are not reliable.

Physiological parameters such as heart rate, respiratory rate and blood pressure lack sensitivity and specificity. Better assessment results from simply asking the patient1.

A departmental culture that encourages patients self reporting of pain and intensity is also encouraged.

A number of scales or tools are available for patients to indicate their pain intensity, response to analgesic agents, or both1.

Verbal Descriptor Scales

When using verbal descriptor scales, simply ask the patient to rate their pain. Choose from:

- No pain

- Mild pain

- Moderate pain

- Severe pain

- Very severe pain

- Worst possible pain

or ask the patient to rate their pain relief. Choose from:

- None

- Mild pain relief

- Moderate pain relief

- Complete pain relief

Numerical and Combined Rating Scales

These include a:

- Visual analogue scales

- Verbal numerical rating scales

- Combined verbal and numerical rating scales

Visual analogue scales

Visual analogue scales are 100mm lines with verbal anchors.

Ask the patient:

‘Please, mark your pain on the horizontal line according to how bad it is, ranging from no pain to pain as bad as it could possibly be’.

Conversely, you may ask your patient:

‘Please, mark your pain relief on the horizontal line ranging from complete pain relief to no pain relief’.

Verbal numerical rating scale

Ask the patient:

‘Please, score your pain on a score from 0 to 10, where 0 is no pain and 10 is the worst possible pain’.

Combined verbal and numerical scale

A combined verbal and numerical rating scale can also be used.

Why use a pain scale at all?

Well, the tools might:

- Get you to consider pain properly in the first place

- Guide your selection of analgesic agents

- Give you an indication of the patients response to pain. Whilst the initial score is subjective, the change in patients pain score gives the assessment more objectivity, the trend having more meaning than the initial score

- Give an indication of departmental performance regarding pain relief through audit

- Provide valid methodology for the research of pain therapies (a visual analogue scale score change of at least 13 mm is required to achieve clinical significance)2.

Which scale should you (or your department) use?

Verbal descriptor scales are quick and simple and lend themselves to the more elderly patient population. However, the choices are limited when compared to numerical rating scales and changes in intensity are not so easily identified.

Numerical rating scales on the other hand offer a wider choice and avoid imprecise descriptive terms. They do require more concentration and coordination. Decent eyesight is also needed for the visual analogue scale.

Further considerations

Do you select a scale for individual patients, or have a one-for-all scale with whom all members of the team are familiar?

And what about children; in particular young children? There is no easy answer you will cover more of this later in this session.

Do also note that the rest pain score may not be the same as when your patient moves, for example the patient with a fractured neck of femur who needs an x-ray, the patient with fractured ribs who needs to cough or the patient with a fractured clavicle who needs to dress and undress.

Pain Scales and Patient Care

So how might pain scoring tools make a meaningful difference to your patients?

In the ideal journey through the ED, your patients pain score is established at triage prompting appropriate analgesic provision. You repeat the patients score on consultation, using the same pain assessment tool prompting reassessment of the patients analgesic needs.

If the consultation is delayed, pain scoring with or without analgesia, is provided by nursing staff.

Frequent pain scoring prompting timely and effective analgesia is simple in theory but not necessarily found in practice. In fact there is reasonable evidence to suggest that mandatory pain scoring (at least at triage) does not necessarily result in adequate analgesic provision3.

Learning Bite

Frequent pain scoring should identify the need for top-up analgesia.

Pain Assessment Tools in Practice

Take time to reflect on the following with regard to pain relief strategies in your own ED:

- Are patients encouraged to report pain?

- What pain assessment tool or tools are in use?

- When and where are pain assessment tools applied?

- Where is the pain score recorded? Is this ideal?

- Are the pain assessment tools appropriate for your ED case-mix?

- When was the last time your department audited its performance regarding analgesic provision?

- What did the audit show?

- What changes were suggested and implemented?

- Was change effective?

Fig 6: Faces pain rating scale used in paediatric cases and the pain ruler

Opiates

Opiate medication is your first choice for analgesia when patients rate their pain as moderate or severe.

RCEM recommends intravenous morphine, 0.1-0.2 mg/kg initially in patients with severe pain. Intramuscular or subcutaneous administration should be condemned, given the delayed absorption via this route and the pain involved in (repeated, perhaps) delivery.

Codeine or tramadol have a role in moderate pain.

Morphine

Morphine is likely to be the most widely used opiate in the ED. It is also the standard with which other opiates are compared.

One of the downsides to opiates in general is the variability in patient response. So do encourage frequent reassessment of pain scores and be prepared to prescribe further increments.

Morphine reaches peak effect within a few minutes when given intravenously and in general provides clinical effect for three to four hours.

Learning Bite

The College recommends intravenous morphine 0.1- 0.2mg/kg initially in patients with severe pain.

Diamorphine

Fig. 7 Diamorphine Hydrochloride (ampule)

Whilst there are no differences between parenteral diamorphine and morphine in terms of analgesia and side-effects, diamorphine can be absorbed (rapidly) by the transmucosal route.

This has given it a proven role intranasally in children4 and is an option in adults with difficult venous access.

Fentanyl

Fig. 8 Fentanyl

The key advantage of fentanyl over morphine is its brief action, providing analgesia for 30-45 minutes, thereby giving it a role in procedural sedation. It can be administered intranasally to adults and is rapidly absorbed by the transmucosal route.

Ultra-short acting opiates have been developed such as remifentanil (duration of action <6 min) and alfentanil (about 10 min).

Whilst there are theoretical benefits, you should consider governance and training issues before using them. Besides, the more widespread use of propofol for procedural sedation is likely to limit the role of ultra-short acting opiates.

Codeine

Recommended by the College, codeine nevertheless has several limitations as an oral opiate:

- It compares poorly with both paracetamol and ibuprofen, even in doses of 60 mg

- Most of its analgesic effect is as a result of metabolism to morphine – nearly 10% of Caucasians and 1-2% of Asians lack the required enzyme

Learning Bite

Codeine compares poorly with paracetamol and ibuprofen, even in doses of 60 mg.

Tramadol

Fig.9 Tramadol hydrochloride (capsules)

Tramadol is widely used in continental Europe. Not all its effects are via opiate receptors.

The maximum dose is 100 mg every four hours.

Tramadol enjoys a much better safety profile than other opiates, notably less risk of respiratory depression.

Common adverse side effects of opiates

- Sedation (hence respiratory depression)

- Nausea and vomiting

- Histamine release causing pruritus and (mild) hypotension

- Slowing of gastrointestinal function (constipation)

- Urinary retention

The adverse effects tend to be dose related.

In general, opiates are metabolised in the liver and excreted in the kidneys. Hence there is a tendency to greater and longer lasting desired and undesired effects from accumulation in patients with liver and kidney dysfunction.

Paracetamol

Paracetamol (acetaminophen in some countries) is an effective analgesic scoring surprisingly well when compared with other agents.

It is also antipyretic, though its mechanism for either effect is not known.

Rectal and intravenous preparations are available.

Avoid using Paracetamol in patients with active liver disease.

Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

- Analgesic

- Antipyretic

- Anti-inflammatory

These result from inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis. Oral, rectal, intravenous and topical preparations are available.

Side effects

NSAIDs have a number of side-effects:

- Peptic ulceration. For those patients at risk of ulceration (and who really need the NSAID) the British National Formulary recommends you consider prescribing a proton pump inhibitor, an H2-receptor antagonist such as ranitidine given at twice the usual dose, or misoprostol

- Renal impairment (particularly when given to patients with pre-existing renal impairment or hypotension)

- Bronchospasm in a small percentage of asthmatics (typically those with chronic rhinitis and nasal polyps)

- Inhibition of platelet function with some evidence of increased blood loss following surgery5

Learning Bite

No good evidence exists suggesting any NSAID is superior. Ibuprofen is the safest, cheapest and most readily available over the counter.

Musculoskeletal pain

Scenario: A 27-year-old male cyclist presents with an isolated fractured left femur, having been hit by a car. The paramedics have given 10 mg IV morphine, entonox and splinted his leg. His verbal pain score is 6.

Suggested best practice: Severe musculoskeletal pain

Titrated intravenous morphine is recommended, with some adults requiring doses in excess of 20 mg.

There is no need for prophylactic anti-emetics, given the low (<4%) incidence of opiate-related nausea in patients with musculoskeletal injury [6].

You should check for a dislocated joint and if confirmed, prompt reduction with procedural sedation is ideal and is covered in another session.

Correcting significant angulation of a long bone and splinting is a first aid measure for haemorrhage control, normally performed by paramedic colleagues at the scene. If overlooked, you should act, using nitrous oxide (70% if available) as a minimum.

Regional anaesthesia has a role in specific injuries:

- 3 in 1 block (femoral nerve, obdurator nerve and lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh) or fascia iliaca block for a fractured femur. There is no evidence of a delayed diagnosis of compartment syndrome as a result [7]. Their clinical effect in fractured neck of femur is less [8]

- Thoracic epidural for fractured ribs, particularly in patients with chronic lung disease

Paracetamol may reduce overall opiate requirements. NSAIDs are best avoided if open reduction and internal fixation is planned and/or in the elderly or hypotensive/hypovolaemic patient.

You must consider compartment syndrome in patients with significant pain, especially on passive movement despite 20mg or so of morphine.

Suggested best practice: Mild to moderate musculoskeletal pain

Fig 10: Example of a minor fracture: Anterior and sagittal radiograph showing a minor fracture to wrist

Paracetamol, with or without ibuprofen, is recommended in the first instance.

Top-up with opiates as required, with tramadol the likely better option. Physical aides have a role:

- Ankle strapping

- Compression support (Tubigrip) for knees

- Slings and splints for upper limb injuries

Early movement is encouraged especially for neck, back and shoulder soft tissue injuries.

Special musculoskeletal case: Calcitonin

Fig 11: Sagittal radiograph showing osteoporosis related vertebral fractures

Calcitonin is effective in the treatment of acute pain after osteoporosis related vertebral fractures [9].

Chest Pain

Scenario: A 56-year-old female presents with central crushing chest pain consistent with acute coronary syndrome. PR 105, BP 160/90; she is grey and clammy. The paramedics have given her 10 mg morphine IV, 10 mg metoclopramide IV, two sprays of GTN and aspirin 300 mg orally. She has subsequently vomited. Her verbal pain score is 7.

Suggested best practice:

In order to decrease pain and limit myocardial damage, the goals in acute coronary syndrome are to:

- Optimise oxygen delivery

- Decrease myocardial consumption

- Restore coronary blood flow

A combination of high flow oxygen, nitrates and morphine is the mainstay of treatment whilst STEMI, NSTEMI or an alternative diagnosis is established by ECG. Patients with STEMI need prompt thrombolysis or PCI depending on local practice.

General advice is for titrated IV nitrate, if there is no resolution of symptoms from three sublingual doses [10]. You should note that the starting IV infusion rate normally stated (2-4 ml/hr of a 50 mg/50 ml neat solution) is low, effectively a rate of 33-66 g/min compared to 400 g per sublingual dose. Therefore start low but increase the rate every two minutes or so to effect.

Hypotension is a recognised side effect from the generalised vasodilation caused by the nitrate, morphine and perhaps thrombolytic.

Consider leg elevation and fluid boluses before reducing or stopping the nitrate infusion. Nitrates are contraindicated in patients relying on adequate venous return, e.g. those with aortic stenosis or right ventricular infarct.

Consider a prophylactic IV anti-emetic, avoiding cyclizine which may increase heart rate and therefore myocardial oxygen consumption.

Nitrous oxide is rarely used in this scenario in UK practice (personal opinion) but has a proven role.

For STEMI patients, consider beta-blockers (metoprolol 50 mg) or calcium channel blockers (diltiazem 60 mg), particularly if your patients heart rate or BP remain high [11].

Cocaine-associated chest pain

With cocaine-associated chest pain, strongly consider the use of IV benzodiazepines and nitrates titrated to effect [12].

Abdominal Pain

Scenario: A 19-year-old male presents with appendicitis and clinical examination supports this. He has been given entonox by the paramedics and has vomited. His verbal pain score is 4.

Common myths to dispel

- Opiates mask the signs and symptoms of abdominal pathology and should be withheld until the diagnosis is established. In fact, adequate analgesia probably enhances the diagnostic process by improving patient cop-operation with the examination (13-14)

- Morphine should be avoided in pancreatitis because it increases the tone of the sphincter of Oddi. Technically true and proven in animal and human experimental models. Just like other opiates, pethedine included. There are no clinical studies comparing opiods in the treatment of biliary spasm or acute pancreatitis.

Suggested best practice

Titrated IV morphine. In general, adding intravenous paracetamol might reduce opiate requirements. NSAIDs (e.g. IV ketorolac) are at least as effective as parenteral opiates for biliary colic and more effective than hyoscine butylbromide (Buscopan ) [5]. Whilst NSAIDs are a reasonable choice in high probability biliary colic (patient awaiting cholecystectomy), you should avoid them in undifferentiated RUQ/epigastric pain (potential peptic ulceration).

Renal colic

Fig 12: Axial CT showing a renal stone

While NSAIDs are at least as effective as parenteral opioids [15], personal preference is to use both simultaneously IV morphine bolus and IV ketorolac with supplemental IV morphine as necessary.

Dysmenorrhoea

Try ibuprofen and vitamin B1 [16].

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

Try antispasmodics hyoscine butylbromide (Buscopan ) or peppermint oil [5].

Other Painful Scenarios

Burns

There is a limited evidence base for the management of pain in burn injuries [5].

Cooling the burn immediately after injury is a first aid measure that limits injury and provides relief.

On presentation to the emergency department (ED) you should aim to assess the depth and size of burn on designated charts promptly, so as to allow the burn to be covered (Clingfilm, Jelonet), an analgesic manoeuvre in itself.

Titrated intravenous morphine is otherwise the key (Fig 1). Paracetamol and ibuprofen may reduce opiate requirements.

Sickle cell crises

Fig 13 Sickle cell anaemia

Titrated IV morphine is recommended with, ideally, patient controlled analgesia thereafter. Under prescribing in young black males may be a real issue.

Supplemental oxygen has not been shown to decrease the pain or duration of a crisis [5].

Single dose parenteral ketorolac does not reduce opiate requirements [5].

A Cochrane review confirms that parenteral corticosteroids shorten the period of analgesic requirement and hospital length of stay in a sickle cell crisis.

Migraine

Fig 14 Migraine a possible cause

Triptans are highly effective in the treatment of severe acute migraine where simple analgesia has failed.

Subcutaneous injections and nasal sprays provide the fastest symptom relief and higher efficacy, particularly in the presence of nausea and vomiting.

Oral triptans are better tolerated but take longer to act and are less reliable [5].

Parental metoclopramide, chlorpromazine and prochlorperazine are also effective treatments in the ED. Opiates have limited benefit and their use is not recommended [5].

Cluster headaches

Fig 15 Cluster headaches a possible cause

Cluster headaches are associated with dilation of blood vessels and inflammation of nerves behind the eye.

Subcutaneous sumatriptan injection and intranasal sumatriptan spray are effective.

Oxygen therapy, 7-10 L/min for 15 minutes can be used alternatively, or in addition [5].

Pain out of proportion

Fig 16: Fractured tibia complicated by compartment syndrome

Beware

Compartment syndrome may complicate injuries of the forearm, foot, thigh, upper arm and indeed abdomen, as well as a fractured tibia.

A Lisfranc injury (fracture/dislocation of the midfoot) is an important injury that might be overlooked on traditional x-rays. Clue: excessive pain. Ask for a lateral foot x-ray to aid your diagnosis.

Painful +++ cellulitis? Think necrotising fasciitis.

Difficult communication with patients

These patients include young children (covered elsewhere), the deaf, the mute, the confused, those with learning difficulties and those with limited understanding of the English language.

All of these patients may be in pain, regardless of the reason for their presentation. While angulated or shortened long bones are obvious indicators of pain, you may not so easily establish the existence of occult fractures, head, chest or abdominal pain.

So what are the possible solutions?

- Listen to family members and carers

- Seek the opinion of nursing colleagues

- Look for physiological clues, e.g. increased heart rate, increased BP

- Provide appropriate tools: an interpreter, multilingual printed information, pain measurement scales, someone proficient in sign language for the deaf, a dedicated learning needs nurse, a writing board for the mute, are some examples

- Titration of analgesic therapy

- Common sense

The elderly

Much of the previous discussion (patients in whom communication is difficult) applies. In addition, it is important to remember:

- Verbal descriptor scales may be more reliable than visual analogue scales

- Opiate requirements in general are less but significant inter-patient variability persists

- NSAIDs should be avoided. If you must, try a short course of ibuprofen 200 mg three times a day, consider gastroprotection and make them aware of the side-effects

Treatment

Consider:

- Carefully titrated IV morphine for severe pain, starting with a lower initial bolus, e.g. 2 mg and allowing three to four minutes between top-up doses

- Paracetamol as the non-opiate of choice

Learning Bite

NSAIDs should be avoided in the elderly. Start with a lower initial bolus of 2 mg of titrated IV morphine for severe pain in the elderly.

The Unconscious patient

Consider the following two scenarios:

- The multiple-injured young male who is paralysed and ventilated and set for the CT scan

- The elderly warfarinized female with a likely non-traumatic intracranial haemorrhage having presented with a GCS of 4

Treatment

Scenario 1

The propofol infusion of the first patient has no analgesic properties. An IV bolus of morphine may reduce pain perception and therefore reduce propofol requirements (and associated propofol related hypotension). If the patient were tachycardic and remained so post opiate, this would support hypovolaemia as a potential cause rather than pain.

Scenario 2

This patient may well be for tender loving care, CT scan optional. It would be in her interest to give 1-2 mg of morphine for comfort and check for and address a full bladder.

Patients with chronic pain

Patients with chronic pain can develop new symptoms and should be evaluated accordingly. Likewise patients with proven malignancy, e.g. pathological fracture.

Treatment

You should use opiates as required, with no particular ceiling.

Consider involving specialist teams such as the pain team or palliative care.

Patients who routinely use illicit drugs

From the patients perspective and in particular in those using intravenous drugs:

- They are more vulnerable to disease and injury

- They may be perceived as drug seeking, even when they have a genuine illness

- They are likely to suffer withdrawal symptoms if their opiate (or other drug) requirements are not met

Treatment

- Consider these patients as high risk of pathological disease or injury

- Do not label them as drug seeking, unless there is clear evidence of well-being (normal observations, normal examination)

- Use titrated IV opiates to address acute pain

- Continue methadone (e.g. 30 mg a day)

- Engage the help of the pain team

- Analgesic agents act at different sites; the use of several agents might reduce the total dose needed of any individual agent, with a resultant decrease in side-effects

- Verbal descriptor scales might be suitable for the elderly

- Frequent pain scoring should identify the need for top-up analgesia

- The College recommends intravenous morphine 0.1- 0.2mg/kg initially in patients with severe pain

- Codeine compares poorly with paracetamol and ibuprofen, even in doses of 60mg

- No good evidence exists suggesting any NSAID is superior, ibuprofen is the safest, cheapest and readily available over the counter

- Start IV nitrate therapy for ischaemic chest pain if there is no resolution of symptoms from three sublingual doses

- Morphine does not mask the signs of abdominal pathology

- NSAIDs should be avoided in the elderly

- Start with a lower initial bolus of 2mg titrated IV morphine for severe pain in the elderly

- If the pain score is out of keeping with the clinical findings, reconsider your diagnosis: what are you missing? Think compartment syndrome, missed dislocation, necrotising fasciitis

- Gallagher EJ, Liebman M, Bijur PE. Prospective validation of clinically important changes in pain severity measured on a visual analog scale. Ann Emerg Med. 2001 Dec;38(6):633-8.

- Jadav MA, Lloyd G, McLauchlan C, Hayes C. Routine pain scoring does not improve analgesia provision for children in the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2009 Oct;26(10):695-7.

- Kendall J M, Reeves B C, Latter V S. Multicentre randomised controlled trial of nasal diamorphine for analgesia in children and teenagers with clinical fractures. BMJ 2001; 322 :261

- medicine.ox.ac.uk

- Acute Pain Management: Scientific Evidence. Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (ANZCA) and Faculty of Pain Medicine, 2020.

- Bradshaw M, Sen A. Use of a prophylactic antiemetic with morphine in acute pain: randomised controlled trial. Emerg Med J. 2006 Mar;23(3):210-3.

- Carley S. IVRA (Biers block) is better than haematoma block for manipulating Colles fractures. BestBets, 2000. Updated: 2005.

- Fletcher AK, Rigby AS, Heyes FL. Three-in-one femoral nerve block as analgesia for fractured neck of femur in the emergency department: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2003 Feb;41(2):227-33.

- Blau LA, Hoehns JD. Analgesic efficacy of calcitonin for vertebral fracture pain. Ann Pharmacother. 2003 Apr;37(4):564-70.

- Gibler WB, Cannon CP, Blomkalns AL, Char DM, et al. Practical implementation of the guidelines for unstable angina/non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in the emergency department: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology (Subcommittee on Acute Cardiac Care), Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, and Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group, in Collaboration With the Society of Chest Pain Centers. Circulation. 2005 May 24;111(20):2699-710..

- Pollack CV, Antman EM, Hollander JE. 2007 Focused Update to the ACC/AHA Guidelines for the Management of Patients With ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction: Implications for Emergency Department Practice. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 2008; 52:344-355.e1.

- Baumann BM, Perrone J, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of diazepam, nitroglycerin, or both for treatment of patients with potential cocaine-associated acute coronary syndromes. Acad Emerg Med. 2000 Aug;7(8):878-85.

- Manterola C, Astudillo P, et al. Analgesia in patients with acute abdominal pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Jul 18;(3):CD005660.

- McHale PM, LoVecchio F. Narcotic analgesia in the acute abdomena review of prospective trials. Eur J Emerg Med. 2001 Jun;8(2):131-6.

- Holdgate A, Pollock T. Systematic review of the relative efficacy of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and opioids in the treatment of acute renal colic. BMJ 2004; 328 :1401

- Marjoribanks J, Proctor ML, Farquhar C. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for primary dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(4):CD001751. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001751. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD001751.