Author: Katherine Henderson / Editors: Clifford J Mann, Lou Mitchell / Reviewer: Thomas Mac Mahon, Mehdi Teeli / Codes: / Published: 21/01/2022

Context

Approximately 27,000 transient ischaemic attacks (TIAs) occur each year in England; this is likely to be a conservative estimate [1].

Making the diagnosis of TIA is important because the patient is at high risk of suffering a disabling stroke.

In England and Wales, over 80,000 people are hospitalised with, and 11% of deaths are attributable to, stroke. One-third of acute stroke patients are left dependent on others for daily activities and, in consequence, cerebrovascular disease is the third leading cause of disability in the UK.

Emergency physicians have an opportunity to recognise patients who have had a TIA and ensure they are promptly treated and investigated, thereby reducing the proportion that will suffer a stroke.

Definition

Traditional definition: time-based

Transient ischaemic attack (TIA) is traditionally defined as an acute loss of focal cerebral or ocular function with symptoms lasting less than 24 hours, and which is thought to be due to inadequate cerebral or ocular blood supply as a result of low blood flow, thrombosis or embolism [1].

However, this definition poses practical difficulties in acute clinical practice.

The 24 hour cut-off for definition is arbitrary. Most TIAs last less than 1 hour, with a median duration of 14 minutes in patients presenting with carotid artery territory symptoms, and 8 minutes in those with vertebrobasilar ischaemia. Only 2% of patients whose symptoms do not rapidly improve within 3 hours had complete resolution at 24 hours [6].

Furthermore, infarction can be present despite complete resolution of symptoms. MRI studies of patients with TIA have shown that up to 50% of those who have fully recovered within 24 hours have abnormalities seen on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) of the brain [7]. In one study, symptoms lasting more than or equal to one hour were independently correlated with abnormal findings on DWI MRI [8].

New definition: tissue-based

As a consequence of these observations, in 2002 a proposal was made for a new definition:

A TIA is a brief episode of neurologic dysfunction caused by focal brain or retinal ischaemia, with clinical symptoms typically lasting less than 1 hour, and without evidence of acute infarction [6].

This definition may help to differentiate TIA from minor stroke and stroke mimics. However, the change remains controversial, principally due to challenges around access to imaging.

In practice the precise definition used is not of great importance as however quickly or slowly recovery occurs and whether or not there is evidence of permanent damage on brain imaging, the investigations and medical treatment will be broadly similar [1].

In 2007, the average stroke risk within 7 days of a TIA was estimated at 5.2%, with the risk ranging up to 12.8% in some studies[2]. Risk is highest within 48 hours of a TIA.

Substantial evidence was produced to show that active intervention for patients at high risk of stroke recurrence would reduce this risk. The EXPRESS study for example reported a highly significant reduction in the 90-day recurrent stroke rate in patients seen in the open access study clinic (4.4% vs 12.4%; p<0.0015) [3].

More recent work has suggested that this risk of early stroke after a TIA has approximately halved, which may reflect the benefits of aggressive secondary prevention pursued over the last decade [4]. Nevertheless, all suspected cerebrovascular events need to be investigated and treated urgently.

Emergency physicians should focus on the assessment of short term risk as this determines whether a patient needs immediate inpatient work-up or can be managed as an outpatient at an early access clinic.

By using a validated scoring system to evaluate risk, emergency physicians can identify and manage these patients effectively.

It is important to bear in mind the local availability of services. The UK National Sentinel Stroke Audits have shown that there is marked variation in service provision across the country. Data published in 2016 showed that only 73% of TIA clinics in the UK can see high risk TIA patients within 24 hours, 7 days a week, and can see low risk patients within a week [5]. This may limit the options available to emergency physicians for subsequent patient management.

Introduction

Transient ischaemic attack is part of a patho-physiological continuum of cerebrovascular disease.

An acute TIA is the clinical consequence of an interruption of the blood supply to a focal part of the brain with consequent disruption of function. In TIA this disruption is temporary.

Main causes of TIA

TIAs result from one of three main aetiologies:

- Large artery atherosclerotic infarction e.g. carotid artery disease

- Small vessel disease e.g. striate arteries

- Embolism from a cardiac source e.g. left atrial appendage in atrial fibrillation

Other causes of TIA

Other causes can include:

- Dissection

- Hypercoagulable states

- Sickle cell

In some patients, the aetiology is undetermined.

The neurological symptoms and signs will reflect which vascular territory has been affected.

Risk Factors

Strong

Atrial fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation causes stasis in the left atrium, which increases the chance of thrombus formation in the left atrial appendage. Thrombus once formed inside the heart can embolise, creating TIA or stroke.

Valvular Disease

The mechanism of association is likely to be due to valve abnormality forming a thrombogenic focus in the heart and thus predisposing to embolic events.

Carotid Stenosis

Higher rates of stenosis (>70%) are associated with significantly increased risk compared with moderate stenosis (50% to 69%).

Congenital Heart Diseases

This may be due either to stasis, leading to increased risk of cardioembolic events, or via common risk factors for cerebrovascular disease and ischaemic heart failure.

Hypertension

The most common risk factor for cerebrovascular disease.

Relative risk for TIA is approximately 2- to 5-fold in the presence of hypertension.[16} The higher the chronic BP elevation, the more this risk factor is important for cerebral ischaemia, forming a continuous risk association.

Mechanism is via increasing likelihood of atherosclerotic vascular disease.

Diabetes

Diabetes is a potent risk factor for atherosclerotic disease and has been reported to be present in up to one third of patients who present with cerebral ischaemia.[17] The presence of diabetes increases the risk for TIA by an odds ratio of 1.5 to 2.[16]

Diabetes is frequently associated with other atherosclerotic risk factors in the metabolic syndrome. It is recommended that the patient with diabetes be recognised to be at greater than average risk for cerebrovascular disease. As a result, patients with diabetes are felt to merit aggressive management of other modifiable risk factors.

Smoking

Alcohol

Strong association for heavy use only. The relationship between alcohol use and stroke is non-linear with higher risk with heavy use, but a relative protective effect with moderate alcohol intake.[18]

Moderate alcohol use may increase protective levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and decrease platelet aggregation. Intake of >60 g of alcohol daily is associated with an increased risk of ischaemic stroke with an odds ratio of 1.6.[18]

Advanced age

TIAs are more common in middle age and in older people. Symptoms in a young patient increase the possibility of alternative diagnosis or a less common aetiology for ischaemia, such as congenital heart disease, paradoxical emboli, drug use, or hypercoagulability.

Weak

- Hyperlipidaemia

- patent foramen ovale

- inactivity

- Obesity

- Hypercoagulability

Stroke Causes

Introduction to Circulation

This image shows the circulation regions of the brain.

The anterior circulation is served by the internal carotids, which supply blood to the anterior 3/5 of the cerebrum. The main branches of the internal carotids are the:

- Middle cerebral artery (MCA)

- Anterior cerebral artery (ACA)

The posterior circulation is served by:

- The vertebrobasilar arteries which supply the posterior 2/5 of the cerebrum, part of the cerebellum and the brain stem

- The basilar artery which gives off the posterior cerebral arteries (PCA)

The anterior and posterior circulations are linked via posterior communicating arteries forming the Circle of Willis. The precise area supplied by each artery varies between individuals, as does the presence or absence of collateral vessels.

The symptoms of TIA in the anterior circulation (carotid/ACA/MCA) are:

The symptoms of TIA in the anterior circulation (carotid/ACA/MCA) are:

- Weakness or sensory loss affecting the contra-lateral arm, leg or one side of the face

- Dysphasia or dysarthria (dysphasia usually indicates left sided cerebral hemisphere ischaemia)

- Monocular visual loss (amaurosis fugax) usually lasting a few minutes only (ophthalmic branch of internal carotid)

In differentiating between anterior and middle cerebral artery occlusions, it should be noted that:

- Middle cerebral artery occlusion affects the contra-lateral face and arm more than the leg. See homunculus diagram to the right.

- Anterior cerebral artery occlusion affects the contra-lateral leg more than the face or arm

- In lesions affecting the internal capsule (i.e. small vessel disease), the face, arm and leg may be equally affected as the relevant nerve fibres lie close together.

The symptoms of TIA in the posterior circulation (vertebrobasilar system, PCA, cerebellum) include:

- Bilateral motor and/or sensory deficits

- Cortical blindness

- Diplopia

- Vertigo (although not usually in isolation)

Why posterior circulation TIAs may be difficult to diagnose

Posterior circulation TIAs may be difficult to diagnose because of the similarity of symptoms with more benign conditions, such as labyrinthitis or benign paroxysmal positional vertigo.

Suspicion, assessment of risk factors and referral for imaging (MRI) through your local TIA workup system may be the only way of making the diagnosis.

Clinical information to guide treatment has been less available because of difficulties imaging the posterior circulation.

Symptoms of posterior circulation TIAs

Posterior circulation TIAs can have a variety of symptoms because the posterior circulation supplies:

- Brain stem

- Midbrain

- Cerebellum

- Thalamus

- Parietal and occipital cortex.

Symptoms should represent focal neurology and be understandable by considering the possible vascular territory.

TIA origin in the posterior circulation may occur as a result of large vessel or small vessel ischaemia.

Large vessel vertebrobasilar TIAs may be due to large vessel atheroma or dissection, or emboli from the heart or aortic arch.

Important symptoms are:

- Vertigo

- Diplopia

- Nausea and vomiting

Risk of stroke

As with anterior circulation TIAs, patients with posterior circulation TIAs have a significant risk of suffering a stroke in that territory, which may be devastating. The clinical approach to posterior circulation TIAs should be the same as that for anterior TIAs.

There may be some future in vertebrobasilar stenting procedures.

Clinical Assessment

The acute diagnosis of TIA is based on clinical history. Witness accounts are useful, but may not be available.

If a patient still has neurological symptoms when they are seen in the ED, it is more probable that they have had a stroke.

Important points to establish from the history are:

- The time of symptom onset and the duration of symptoms

- Associated symptoms

- Past medical history of co-morbidities associated with increased risk for TIA and CVA

- Past medical history of possible causes of neurological deficit other than TIA e.g. malignancy

In order to differentiate from stroke mimics, it is important to ascertain the following:

- The symptoms are acute in onset

- Symptoms reach maximum intensity within seconds

- Symptoms all begin at the same time

- There may be single or multiple episodes

Learning bite

A typical TIA will present with risk factors for vascular disease and one of the following:

- Limb weakness as a presenting symptom

- Speech difficulty as a presenting symptom

- Transient monocular loss of vision

- The symptoms are focal

- The symptoms fit with a vascular territory of the brain.

- The symptoms are negative

- Loss of function, as opposed to conditions such as migraine, which produce positive symptoms, for example flashing lights or wavy lines.

TIA symptoms are characterised by a loss of function.

Considerations When Managing Patients with TIA in the ED

When managing patients with TIA in the ED, it is important to consider the aetiology and be able to relate focal neurology to a specific vascular territory.

Some aetiologies are more amenable to treatment aimed at stroke prevention. The key causes to consider are symptomatic carotid stenosis and atrial fibrillation.

Learning bite

Detection of patients with carotid stenosis or atrial fibrillation enables prompt delivery of effective treatment to reduce the probability of a stroke.

The Oxfordshire Community Stroke project demonstrated that the risk of recurrent stroke is greatest in those with large vessel stenosis or atherosclerosis [9].

Major artery stenosis was associated with a stroke risk of 12.6% at 30 days as compared to a 2% risk for patients with small artery stenosis.

In consequence, while only 14% of strokes were caused by large artery atherosclerosis, these patients accounted for 37% of the recurrent strokes within 7 days (compared with 3.3% recurrence in patients with small vessel disease).

This supports the need for urgent carotid imaging and prompt endarterectomy where appropriate.

Scoring Systems

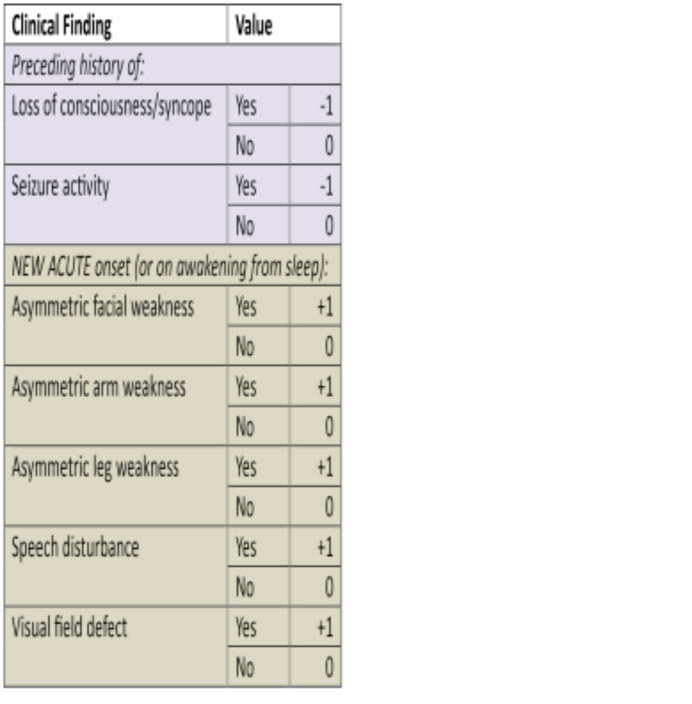

ROSIER Scale

The Recognition of Stroke in the Emergency Room (ROSIER) scale was developed to help in the initial differentiation of acute stroke from stroke mimics in the ED [10].

Table 1: ROSIER Scale

A score of zero or higher showed a sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 83% in prospective validation studies in predicting stroke.

The Canadian TIA Score

The Canadian TIA Score stratifies patients seven day risk for stroke, with or without carotid endarterectomy/carotid artery stenting.

Table 2: Canadian TIA Score

The Canadian TIA score showed an increasing risk with a higher score and when grouped into three risk bands did differentiate into risk groups.

- Score -3-3. Low risk.

- Score 4-8. Medium risk.

- Score 9-14. High risk.

These bandings seem reasonable in terms of risk assessments that might link to clinical strategies relating to discharge or rapid interventions for patients. Low risk being suitable for discharge, but high risk requiring a very rapid intervention to prevent an early stroke

The ABCD scores were unable to identify a low (<1%) risk group and thus the Canadian TIA score appears to have a significant advantage.

The derivation and validation studies for Canadian TIA score appear robust and it appears to offer advantages over our current scores[19].

NICE Guidelines

NICE Guideline (2019) [15] recommends that:

Offer aspirin (300 mg daily), unless contraindicated, to people who have had a suspected TIA, to be started immediately.

Give a proton-pump inhibitor to anyone with dyspepsia associated with aspirin use.

Give clopidogrel as an alternative to aspirin in patients who are allergic or intolerant to aspirin. This is standard practice.

Refer immediately people who have had a suspected TIA for specialist assessment and investigation, to be seen within 24 hours of onset of symptoms.

Do not use scoring systems, such as ABCD2, to assess risk of subsequent stroke or to inform urgency of referral for people who have had a suspected or confirmed TIA. (Evidence showed that risk prediction scores (ABCD2 and ABCD3) used in isolation are poor at discriminating low and high risk of stroke after TIA. Adding imaging of the brain and carotid arteries to the risk scores (as is done in the ABCD2I and ABCD3I tools) modestly improves discrimination. However, appropriate imaging (including MRI) is not available in general practice or for paramedics, 2 of the key situations when these tools would be used. Arranging specialist assessment less urgently for some people based on a tool with poor discriminative ability for stroke risk has the potential for harm. Therefore, the committee agreed that risk scores should not be used.

The committee agreed, based on their clinical experience and the limited predictive performance of risk scores, that all cases of suspected TIA should be considered as potentially high risk for stroke. Also, because there is no reliable diagnostic test for TIA (the risk stratification tools are not diagnostic tests), it is important to urgently confirm or refute the diagnosis of a suspected TIA with specialist opinion. This is particularly so because in practice, a significant proportion of suspected TIA (30% to 50%) will have an alternative diagnosis (that is, TIA-mimic). Therefore, it was agreed that everyone who has had a suspected TIA should have specialist assessment and investigation within 24 hours of the onset of symptoms. The committee noted the results of an original costutility analysis, which was undertaken for this review question in the 2008 version of the stroke guideline (CG68). The analysis concluded that immediate assessment had both better health outcomes and lower costs than assessment within a week for the entire population of suspected TIA, without the use of a risk stratification tool.

The committee acknowledged that having a TIA (or suspected TIA) is a worrying time and most people would prefer to be assessed as soon as possible. Urgent specialist assessment should ensure that people at high risk of stroke are identified early. This would allow preventative treatment to begin, which should be introduced as soon as the diagnosis of TIA is confirmed.

Offer secondary prevention, in addition to aspirin, as soon as possible after the diagnosis of TIA is confirmed.[15]

Introduction

In the ED, a diagnosis of TIA is based on the history, and the physical examination should confirm that neurological symptoms have resolved. The rest of the physical examination should focus on causes for TIA, especially evidence of cardiovascular disease. Standard investigations should include:

- FBC

- U&E

- Plasma glucose

- Lipid profile

- Electrocardiogram

- LFTs as a baseline if anti-cholesterol medication is to be commenced

- Brain imaging

- Carotid imaging

Brain Imaging

Do not offer CT brain scanning to people with a suspected TIA unless there is clinical suspicion of an alternative diagnosis that CT could detect. [15]

After specialist assessment in the TIA clinic, consider MRI (including diffusion-weighted and blood-sensitive sequences) to determine the territory of ischaemia, or to detect haemorrhage or alternative pathologies. If MRI is done, perform it on the same day as the assessment. [15]

Learning bite

The most appropriate imaging modality for TIA is MRI.

Carotid Stenosis

Carotid imaging

Everyone with TIA who after specialist assessment is considered as a candidate for carotid endarterectomy should have urgent carotid imaging. [15]

Urgent carotid endarterectomy

Ensure that people with stable neurological symptoms from acute non-disabling stroke or TIA who have symptomatic carotid stenosis of 50% to 99% according to the NASCET (North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial) criteria:

- are assessed and referred urgently for carotid endarterectomy to a service following current national standards (NHS Englands service specification on neurointerventional services for acute ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke)

- receive best medical treatment (control of blood pressure, antiplatelet agents, cholesterol lowering through diet and drugs, lifestyle advice).

Ensure that people with stable neurological symptoms from acute non-disabling stroke or TIA who have symptomatic carotid stenosis of less than 50% according to the NASCET criteria, or less than 70% according to the European Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST) criteria:

- do not have surgery

- receive best medical treatment (control of blood pressure, antiplatelet agents, cholesterol lowering through diet and drugs, lifestyle advice).

Ensure that carotid imaging reports clearly state which criteria (ECST or NASCET) were used when measuring the extent of carotid stenosis.

Management Options

Secondary prevention treatments should be started as soon as the diagnosis is confirmed. These treatments are initiated following specialist assessment by the stroke/medical team rather than the ED physician.

Lifestyle modification

- Discussion of individual lifestyle factors, including smoking/alcohol reduction, combined with diet and exercise optimisation.

Medications

- Clopidogrel 300mg loading dose, followed by 75mg daily

- High intensity statin therapy with atorvastatin 20-80 mg daily

- Blood pressure-lowering therapy with a thiazide-like diuretic, long-acting calcium channel blocker or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor

Atrial fibrillation

- Patients in atrial fibrillation should be anticoagulated as soon as intracranial bleeding has been excluded and with an anticoagulant that has rapid onset, provided there are no other contraindications.

Admission or discharge with outpatient care

- The latest RCP Guidelines recommend that all patients with a suspected TIA should be assessed within 24 hours by a specialist neurovascular/stroke physician. You should discuss the implications of this guidance for your local service for ED discharge of patients with TIAs to follow up outpatient care.

Admission or discharge with outpatient care

At discharge from hospital, advise the patient not to drive for 4 weeks due to their early risk of having a stroke, and to return to the accident and emergency department if they develop any new neurological symptoms.

Management Principles

What are the principles underpinning the management of suspected TIA:

- Exclusion of other serious causes for the symptoms

- Antiplatelet therapy

- Identification of carotid stenosis

- Identification of cardiac disease such as AF

- Modification of risk factors such as smoking, hypertension, hyperglycaemia and high cholesterol

Learning bite

The key aspect of management from an ED point of view is enabling the patient to access a system which can deliver effective secondary prevention.

The pitfalls when managing TIA are:

- Failing to diagnose a TIA

- Failing to diagnose a TIA can have serious consequences for the patient i.e. stroke.

- An accurate diagnosis needs a good history and an understanding of neurovascular anatomy.

- Mistakenly diagnosing a TIA

- It is important to recognise that non-focal signs are not typically a feature of TIAs. The table below highlights this:

| Typical features – Focal signs | Non TIA symptoms |

|

|

Posterior circulation TIAs

The diagnosis of a posterior circulation TIA may be missed if the possibility is not considered.

Carotid artery dissection

Carotid artery dissection can present with either stroke or TIA symptoms.

It is an important cause to consider in patients younger than 50 years, and accounts for up to 25% of ischemic strokes in young and middle-aged patients.

The mean age for ischaemic stroke, secondary to internal carotid artery dissection from blunt traumatic injury, is even younger at 35-38 years old. Head or neck trauma, including manipulation by a chiropractor, is often a precipitating factor.

There is usually a history of ipsilateral head, face or neck pain.

The neck pain is usually sudden, severe and persistent. A partial Horner syndrome (ptosis with miosis but no anhydrosis), is present in 36-58% of patients. Typical cardiovascular risk factors may be absent.

If suspected, immediate investigation is needed, either CT angiography or MRA.

The neck pain is usually sudden, severe and persistent. A partial Horner syndrome (ptosis with miosis but no anhydrosis), is present in 36-58% of patients. Typical cardiovascular risk factors may be absent [14].

- Royal College of Physicians, National clinical guideline for stroke. Prepared by the Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party. 2016, Royal College of Physicians: London.

- Giles MF, Rothwell PM. Risk of stroke early after transient ischaemic attack: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2007 Dec;6(12):1063-72.

- Rothwell PM, Giles MF, Chandratheva A, Marquardt L, et al. Effect of urgent treatment of transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke on early recurrent stroke (EXPRESS study): a prospective population-based sequential comparison. Lancet. 2007 Oct 20;370(9596):1432-42.

- Amarenco, P., et al., One-Year Risk of Stroke after Transient Ischemic Attack or Minor Stroke. N Engl J Med, 2016. 374(16): p. 1533-42.

- Royal College of Physicians Care Quality Improvement Department (CQID) on behalf of the Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party, Sentinel Stroke National Audit Programme (SSNAP). Acute organisational audit report. National Report England, Wales and Northern Ireland. November 2016. 2016, Royal College of Physicians: London.

- Albers GW, Caplan LR, Easton JD, Fayad PB, Mohr JP, Saver JL, Sherman DG; TIA Working Group. Transient ischemic attackproposal for a new definition. N Engl J Med. 2002 Nov 21;347(21):1713-6.

- Ay H, Oliveira-Filho J, Buonanno FS, Schaefer PW, et al. Footprints of transient ischemic attacks: a diffusion-weighted MRI study. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2002;14(3-4):177-86.

- Crisostomo RA, Garcia MM, Tong DC. Detection of diffusion-weighted MRI abnormalities in patients with transient ischemic attack: correlation with clinical characteristics. Stroke. 2003 Apr;34(4):932-7.

- Lovett JK, Coull AJ, Rothwell PM. Early risk of recurrence by subtype of ischemic stroke in population-based incidence studies. Neurology. 2004 Feb 24;62(4):569-73.

- Nor AM, Davis J, Sen B, Shipsey D, et al. The Recognition of Stroke in the Emergency Room (ROSIER) scale: development and validation of a stroke recognition instrument. Lancet Neurol. 2005 Nov;4(11):727-34.

- Johnston SC, Rothwell PM, Nguyen-Huynh MN, et al. Validation and refinement of scores to predict very early stroke risk after transient ischaemic attack. Lancet. 2007 Jan 27;369(9558):283-92.

- Perry JJ, Sharma M, Sivilotti ML, Sutherland J, et al., Prospective validation of the ABCD2 score for patients in the emergency department with transient ischemic attack. CMAJ. 2011 Jul 12;183(10):1137-45.

- North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators, Barnett HJM, Taylor DW, et al., Beneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with high-grade carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1991 Aug 15;325(7):445-53.

- Lee WW, Jensen ER. Bilateral internal carotid artery dissection due to trivial trauma. J Emerg Med. 2000 Jul;19(1):35-41.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Stroke and transient ischaemic attack in over 16s: diagnosis and initial management. NICE guideline [NG128]. 2019.

- Sacco RL. Risk factors for TIA and TIA as a risk factor for stroke. Neurology. 2004 Apr 27;62(8 Suppl 6):S7-11.

- Woo D, Gebel J, Miller R, et al. Incidence rates of first-ever ischemic stroke subtypes among blacks: a population-based study. Stroke. 1999 Dec;30(12):2517-22.

- Reynolds K, Lewis B, Nolen JD, Kinney GL, Sathya B, He J. Alcohol consumption and risk of stroke: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2003 Feb 5;289(5):579-88.

- Perry J, Sivilotti, MLA, Emond M, et al. Prospective validation of Canadian TIA Score and comparison with ABCD2 and ABCD2i for subsequent stroke risk after transient ischaemic attack: multicentre prospective cohort study. BMJ 2021;372:n49.