Author: Charlotte Davies / Questions: Charlotte Davies / Codes: / Published: 06/02/2018

Back pain is really common in the emergency department and it is vital that we manage it properly. There are many pitfalls around back pain, but prompt and accurate assessment aids prognosis and recovery. Here are ten steps to managing most back pain in the emergency department safely.

- Take a good history

I know everyone says this, but it’s really important to take a history. It’s only by taking a history that you know that, actually, the “fall down stairs” was really a fall over the banisters, dropping 20 foot onto the floor. If your history is worrying for significant trauma, assess the patient as you would any major trauma patient – they’re likely to need a CT! Remember, the elderly don’t need significant mechanism of injury – if they’ve fallen from standing, request a senior review.

Likewise, if your patient says “I was diagnosed with cancer a year ago, and now I have really bad back pain”…you’re going to think about metastases. Back pain radiating to the groin…think aortic aneurysm. Back pain in an IVDU…think discitis. Ask the questions and never assume it’s “just musculoskeletal”.

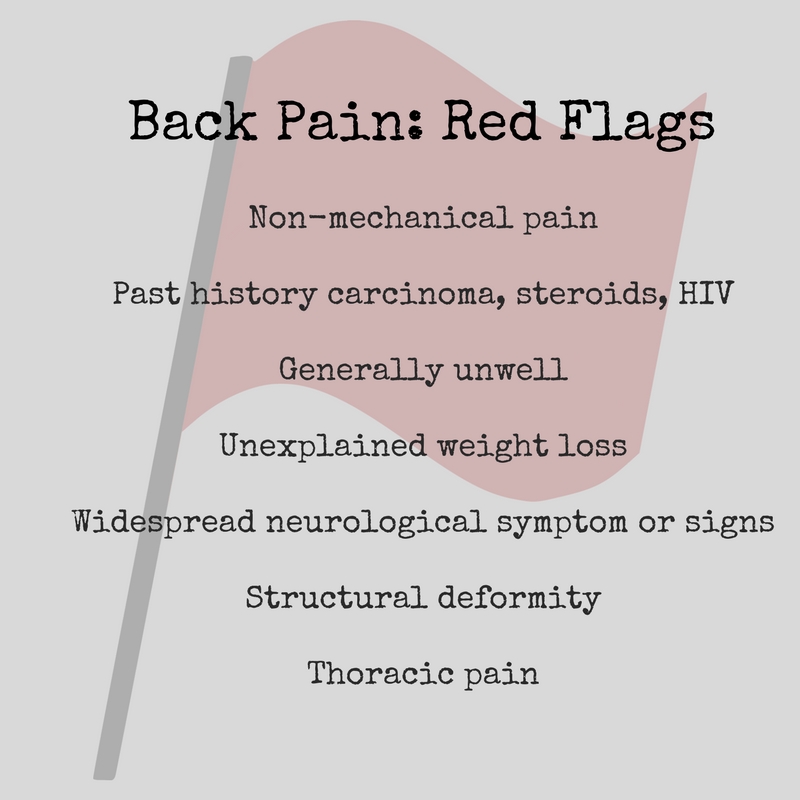

There are red flags for back pain – if you take a careful history you will elicit these.

Age <20 years or >55 years has also been considered a red flag, but non-specific back pain is not uncommon in these age groups. However, significant trauma may raise the possibility of vertebral fracture.

If there are no red flags and you’re thinking that this is musculosketal pain, pause, and consider cauda equina syndrome. Cauda equina is one of the big “don’t miss” diagnoses and by taking a careful history you will know if there’s urinary retention, sexual dysfunction, loss of sensation, loss of anal tone, bilateral sciatica etc.

One of the most common consults we see in neurosurgery is the 'cauda equina syndrome (CES) rule-out.' CES can be diagnostically challenging & panic-inducing due to its highly variable presentation & grave consequences if missed.

— Kristen Scheitler, MD (@k_scheitler) May 13, 2022

How to evaluate suspected CES: a thread ?

(1/9) pic.twitter.com/7Olzd3RZ1V

There are also yellow flags, or risk factors for developing and/or maintaining long-term pain and disability. Once you’ve identified them you can gently start to correct some of the misplaced ideas and address some confounding issues:

– Belief that pain and activity is harmful – encourage your patient to move!

– Belief that pain will persist

– Sickness, avoidant and excessive safety behaviours (like extended rest, guarded movements)

– Low or negative moods, anger, distress, social withdrawal

– Treatment that does not fit with best practice

– Claims and compensation for pain-related disability

– Problems with work, sickness absence, low job satisfaction

– Overprotective family or lack of support

– Placing responsibility on others to get them better (external locus of control)

- Examine Carefully

There’s three reasons to examine patients with back pain carefully.

Firstly, you really do want to know what’s going on. Look at their abdomen in case there’s a pulsatile mass making you think of an aortic aneursym, or making you suspicious of an undiagnosed carcinoma causing metastasis. Look at their general health – is there some neglect?

Then focus on their back pain. Look, feel, move. Look at their movement. Look at their neurology, and consider documenting it carefully on an ASIA chart. Feel for tenderness and worry even if it’s “just” para-spinal. Feel for their sensation. And don’t forget to do the PR (you have to at least offer it). You can even do some special tests like the femoral stretch test if you’re feeling keen – but it isn’t really going to alter your emergency management! Move their back and check their power and reflexes. A careful examination, including neurology, is essential.

Which brings me onto the second reason to examine patients carefully – this is a really high risk legal area. Missing cauda equina has a high cost to the trust (and the patient, and you) – documenting “normal neurology” really won’t cut it. Didn’t do a PR? Inexcusable.

Thirdly, the examination in back pain is your opportunity to begin to treat the patient and start offering reassurance. As you’re going through examining their movements, be positive about their range of movement and (potential) lack of red flags. I learnt a great technique based on Feldendraise – try it for yourself.

- Give proper analgesia and quickly

The quicker you give pain relief, the sooner it can begin to work. The longer patients wait for analgesia, the more tense and frustrated they can get – and the worse their pain gets. Be generous quickly. Every patient with back pain should have paracetamol (even if they say it won’t work), an NSAID (unless contraindicated) and consideration of a weak opiate. Sometimes it’s better to give oramorph than codeine – anything to break the spasm and get the patient moving again. Even chronic back pain needs early analgesia top ups.

Look at our other blog for some suggestions about treatment aims. There’s a sparsity of evidence about all analgesia in back pain – stick to the analgesic ladder and you’ll be OK.

- Think about causes

Most back pain that we see is “simple” back pain. Sometimes, however, we see more complicated back pain, and making sure you identify the cause and the complexity is essential. Your history and examination will have helped you to work out which of these it is.

- Don’t do bloods routinely

The NICE guidelines for back pain management only advise blood tests in complicated back pain. This is excellent advice – when do bloods really change your management in “simple back pain”? Or in many other things, for that matter?

If you do need to do bloods (in complicated back pain) and the bloods are abnormal, think about your cause – again, a high CRP in an IVDU will make you think about a discitis, a high calcium in a patient with a history of weight loss will steer you towards malignancy.

- Don’t do x-rays

As soon as we x-ray patients, we encourage them to come back for x-rays again! The NICE guidelines are really clear – only x-ray if they have risk factors! In young people, backs are really hard to break – so only x-ray them if the degree of trauma is significant. If you’re thinking about x-raying them, just stop and pause and think about whether you should be trauma-calling them and getting CTs instead. The radiation risk from a lumbar spine x-ray is pretty high and needs careful consideration!

It’s in the elderly that x-rays get difficult. The lumbar spine can break spontaneously and x-rays are then very difficult to interpret, but also more likely to show an abnormality. I’m much more likely to image the elderly, as even a low impact may cause significant injury – silver trauma. If in doubt, have a chat with a senior (or a focussed discussion).

- Don’t tell the patient they need an MRI

Imaging is unlikely to be helpful, even MRIs. In asymptomatic people, MRIs show:

– Bulging discs in 20% to 79%

– Herniated discs in 9% to 76%

– Degenerative discs in 46% to 91%.

If you think the patient has cauda equina or spinal cord compression, they obviously need an urgent MRI. If you don’t and they don’t, their GP can review, they can have some physio and go from there. An MRI is only really useful if they are at the stage of potentially needing neurosurgery on their back. Your trust will have a guideline for how to arrange non-emergency MRIs – for us, that’s an admission under orthopaedics.

- Prognosticate and safety net

Don’t tell the patient they’ll be better by tomorrow. Be carefully positive, and give them some good life-style advice (see our other blog).

Tell your patients when to come back. Be clear and precise. Don’t say come back if you’re in pain. Say “come back if the pain is unmanageable at home. Don’t say come back if you have any bladder problems – say return if you can’t pee. You don’t want to see all the patients returning because you’ve made them constipated which has given them a urinary infection and dysuria so they return!

- Refer if needed

If your patient really can’t cope at home with simple analgesia, then they can’t go home. Which specialty they go to will depend on your Trust. It seems sensible that the elderly frail patients with unresolved back pain get admitted under a medical team for pain relief optimisation and good medical care. The young patients with uncontrolled back pain often cause controversy but most hospitals admit them under the care of the orthopaedic doctors, and occasionally under ED in a clinical decisions unit. Know your Trust protocol before you refer – and if you run in to problems, make sure you remember there’s a patient in the middle and escalate to your seniors early.

- Exclude Red Flags

Before you discharge your patient, make sure you’ve really considered whether they have any other pathology. It’s easy to think its musculoskeletal – what are you missing?

This weeks free infographic is ‘Causes of low back pain’. It’s a simple one but hopefully effective. Let me know what you think. Loving creating these and I’m really happy that they are all being used so much. More formats here https://t.co/N8iVKPzCAt #FOAMed #infographic #MedEd pic.twitter.com/tNOQdxc670

Strata5 (@Nrtaylor101) April 16, 2018

Did we mention cauda equina syndrome? Every time you see a patient with back pain, open up the NICE guidelines, and document absence or presence of every single red flag. If there’s a single red flag… … get an MRI. Cauda equina is a neurosurgical emergency – remind yourself of the pathophysiology here or here.

Further Reading: